EVENTIDE .

Catalogue Essay by Eric Henshall, 2020

Nocturne – Art for the night. The night is beautiful. The night is romantic. The night is menacing. And so it is with Meg Cowell’s sumptuous photographic works.

Cowell’s work is undoubtedly beautiful as any star-filled night, but within that beauty lies a subtle sense of menace. Somehow, as we gaze at the luminous glory of these delicate frocks, we feel uneasy - as though we might perhaps be looking at death in a ball gown. The works are lush with rococo splendour – the pastel satins of the gowns are trapped in an eternal, graceful dance. They are romantic images that call to mind candle-lit soirees of Belle Époque elegance; and yet the decadent silks begin to dissipate into smoke at their edges, becoming unreal, immaterial; like Cinderella’s carriage, the façade of beauty is a temporary glamour that quickly evaporates in the light of dawn - or in this case, into the infinite black void.

Acting as momento mori, these sensual dresses are sisters to the smoking skulls in their floral wreaths. The hollow eye sockets and the satin folds all tell us that, ‘Yes, life is beautiful but it is fragile and we will die.’ This intertwining of beauty and death is an enduring theme in Cowell’s work; as is the delicate balance she achieves between the constant, fluid movement of the dresses - they seem alive and vibrant, caught in a single moment - and the unalterable permanence of each and every crease of luxurious fabric - they are as immortal and unbending as the stones of Rome. These fairytale gowns are at once ephemeral and eternal.

The dresses are alive; we can almost hear their heartbeat. But they are unoccupied - where we expect to see a delicately arching neck, an outstretched arm, rosebud lips there is instead only nothing, only that endless black void. It is as though the gowns have consumed their human hosts and somehow grown stronger, and even more exquisite, for it. They are beautiful and lustrous, but these are predatory creatures; pastel-coloured night hunters.

We know this, we sense it, and yet we are enchanted still. Such is the power of Cowell’s work - that knife-edge balance between menace and beauty.

NIGHT BLOOM .

I found her on a night of fire and noise

Wild bells rang in a wild sky

I knew from that moment on

I’d love her ‘til the day I died

Nick Cave, Do You Love Me?

Both revered and adored, the symbol of the Bride is one elevated above the everyday, and brings with it not just an optimistic promise of devotion, but also the reminder of fleeting youth and the complex and sometimes uncertain expectations bound within the marital contract.

The title of Meg Cowell’s latest exhibition, Night Bloom, hints at this paradox, with its suggestion of cool night air and a pull toward moonlight. Within the glossy surfaces of her large format photography, crisply rendered couture wedding gowns float unshackled within infinite blackness. Assigned with cliched titles playfully evocative of cheap romance novels, Cowell’s images tease out the contradictions buried within fairy-tale notions of love.

While her work has always dealt with moments of transition, there is something particularly dark hiding among the folds of Cowell’s latest project. In these new works a real sense of spiritual energy is at play, expressed through her use of cloudy, opalescent waters suggestive of things in a state of vaporous disintegration, and via her still life vanitas’ of faded flowers and human skulls. She says of her aims for this series “I am wanting to capture the hopeful, beautiful, vulnerable flower blooming in harsh uncertain times and terrain. They are almost hysterically romantic”1.

Both beautiful and unsettling, Cowell’s aesthetic channels a filmic sensibility, recalling characters like Margaret Mitchell’s embattled Scarlett O’Hara or Daphne du Maurier's confused and lonely Mrs. De Winter. In perfect Hitchcockian style one starts to wonder if these seemingly perfect images of womanly transformation might in fact be more akin to a dark tragedy. Not quite the grim figure that is Dickens’ Ms Havisham, all faded and torn, or the terrifying spectre of the Wilis 2.that inhabit Giselle’s haunting ballet, Cowell has none the less choreographed a ghostly performance that pays homage to the Victorian Gothic fascination with the afterlife, the supernatural, and the plight of the vulnerable heroine 3.

Cowell’s Night Bloom is telling a story of melancholic romance, in all its dark, succulent allure. It’s a story about youth and beauty, of losing oneself and of falling away from the corporeal. Unlike the majestic hues of her earlier images, the decision to restrict her palette to muted tones and opaque waters suggests ideas of purity, fragility, and the ethereal, and recalls the finely detailed allegorical paintings of the Northern Renaissance. “I am influenced by those Renaissance-era pictures wherein figures are borne up to heaven by clouds. These puffs of celestial vapour communicate a remarkable sense of the supernatural and a tangible expression of divinity” 4.

Where her drapery and cloudy fluids merge, airy space is rendered visible, indicating a slippage between the worlds of the real and the spectral. Dresses defy gravity and fall away into immateriality, as do the objects within her broody still lives. Using artificial flowers, skulls adorned with floral arrangements coalesce with vaporous clouds, suggesting a spirit disembarking or some poisonous gas rising. Reminiscent of the allegorical paintings of the 16th century Dutch School, these images aim to demonstrate the fleeting nature of life, and the inescapable nearness of death.

Whether Cowell is intending to portray the restless soul of a jilted bride or the delighted, passionate dance of a youthful newlywed, Night Bloom taps into something pensive and complex about the nature of romantic love. Within the fairy-tale beauty of these images is hidden a message of fragility, loss and the bittersweet rituals of life's passage.

by Phe Luxford, 2018

Footnotes:

1. Email conversation with the artist, Feb 2018

2. The Wilis appear in the 1842 ballet Giselle. They are the ghostly spirits of maidens spurned by their lovers, doomed to haunt the forests seeking revenge on passing male travellers, enchanting them into a dance till death.

3. The feminine as represented within Gothic literature offers up two stereotypes – the malevolent or the innocent. ‘Women are presented as objects of desire, maternal figures, supernatural beings and are often defined by their biological roles. It is the transition between these typecasts that is particularly interesting.’ Clamp, Rachel, The Significance of Female Identity Within Gothic Literature, https://owlcation.com/humanities/femaleidentity

4. Meg Cowell, Artist Statement 2018

DEEPER WATER .

The allure of Meg Cowell’s work is just as deep and complex as the garments and swell of water that surrounds them within her photographs. Sumptuous, opulent fabrics appear at once to breathe within their own undulations, the inky blackness that envelops them seemingly endless. Inspired by period costume and the hidden meanings often associated with women, status, life experiences and how they shroud themselves, Cowell entrances us with her interpretations.

The artist has always been fascinated with seducing the viewer, through methods of her own construction yet by also embracing chance. While studying her practice she was fortunate enough to have been inspired by talented artists, one of these being the photographer Anne MacDonald, whom Cowell nods to within this latest exhibition. MacDonald is one of those artists described as part of a sub-category of contemporary Australian art, dubbed Tasmanian Gothic. Artists exploring dark truths and folklore surrounding the island– climate shifts, isolation, indigenous slaughter and convict history – create works that are infused with an inclination for the sinister. MacDonald’s work, which looks at showcasing familiar objects lurking in darkness, inspired Cowell. The piece ‘Petals,’ where a soft, blue tinted rose-like petal folds and disappears almost before the viewers eyes is not too dissimilar in form to Cowell’s blue, full dresses. The source of the works is the same, where MacDonald draws often from nature, so does Cowell. Yet where the first artist depicts those inspirations directly, Cowell fuses her gowns with the essence of these ephemeral muses. The artist says, ‘I’ve been looking at elements common to those things considered beautiful in nature; proportion, symmetry clarity, harmony and colour.’ Whilst also looking at Dutch still life painting which captures so brilliantly these exact expressions, Cowell looked to butterflies - their fragility, the aesthetic principals, their deep symbolic resonances – and structured her garments to resemble their forms. The fullness of her dresses appear to take flight, swelling towards the surface and their colours vivid, opalescent, unfading.

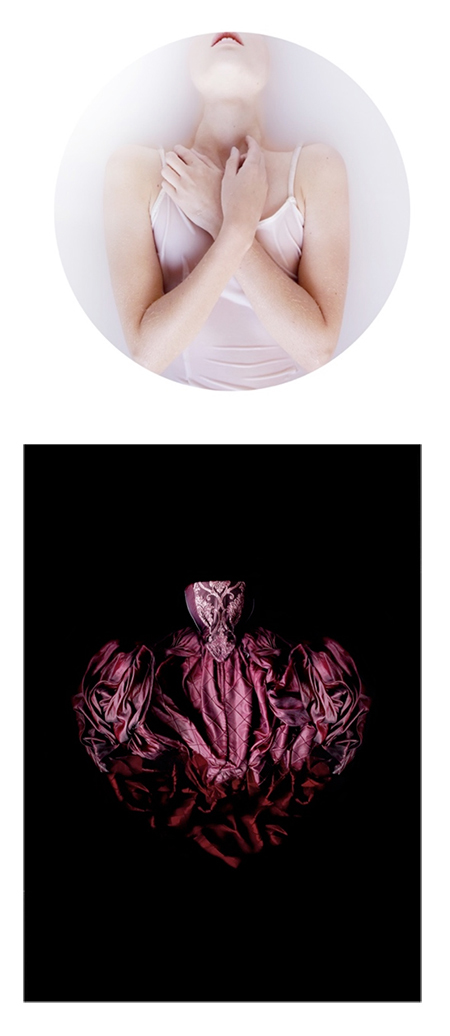

This exhibition for Cowell though is not just a continuation of her exploring these visual pursuits. Where her works have often seemed inhabited, it was a natural progression for the artist to try and document human form within her flowing textiles. Imperative was still the desire to have a strong sense of fragility, and so these new photographs tempt our senses with soft pastel pop tints - colours associated with under garments and lace, and the milkshake hues of youth.

Sally Mann and Bill Henson are perhaps the most famous of photographers to explore these themes – Henson sometimes controversially highlighting a haunting uniqueness that he draws out of his young subjects, and Mann capturing so breathtakingly the freckles and wide eyes of her own children at play.

Cowell too handpicked a model that would perfectly match the beauty that she was trying to grasp. As well as highlighting the often-brutal fashion industry that uses young girls and boys to create a world of fantasy and illusion, Cowell photographed a subject who was bordering the precious moment between childhood and young adulthood. Lithe wrists sit across soft silk, and fingers creep up to touch collarbones – these works are beautiful, disarming and arresting.

There are some photographs where clearly a mature woman is used, and these works too allow for a fascinating reading. Traditional clothing clings across full breasts, partially covered by worked hands and some poses are almost recognisable – the Virgin Mary in her lapis shroud, and Ophelia clutching at flowers at she sinks in to the water beneath her. This move in Cowell’s practice has marked an exciting and haunting shift as she delves into deeper water. Melanie Caple

THE SEA. THE SHORE

“A being dedicated to water is a being in flux.”

Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter

Shakespeare’s infamous Ophelia—broken-hearted, grieving the death of her father—drowns slowly in a river in Denmark. In a state of spiritual collapse, she has fallen from the bough of a tree while collecting flowers. Now submerged, the young woman’s hands puncture the river’s surface like lilies. As she welcomes in death, Ophelia sings, her flaxen dress turning lavender as the water exchanges its initial offering of buoyancy for debilitating weight.

Melbourne based artist, Meg Cowell, photographs undulating feminine garments in, what appears, a vacuum of infinite space. The dresses, rich in hue and excessive in their skirting, are handpicked for their unique and romantic character: “Each garment has to speak to me in some way, to tell me what its wants me to do with it, as cosmic as that sounds.” The chosen articles of clothing are then photographed in a 1000-litre pool Cowell has installed in her inner-city backyard.

Ritual dress accompanies many important rites of passage. For women, white wedding gowns and Victorian mourning attire are iconic artefacts that carry their wearer from one stage of life to the next. In turn, it is not beauty, vanity or a political reading of fashion that concerns Cowell’s practice. Instead, it is the moment when a woman dons a costume for her transformation that is of interest. For the artist, such occasions elevate garments beyond their materiality to become an embodiment of female ritual.

Cowell’s exhibition, The Sea, The Shore, presents a series of large-scale photographic works that illustrate this shift from garment to artefact. Through sophisticated direction, the artist creates vignettes of unique gowns, lingerie and couture as they bloom into new forms: for example, dresses appear flower-like, floating in the abyss. She describes the satisfaction when clothing abandons its inanimate physicality for a sense of agency: “I think an image is successful when it shows metamorphosis. Good images require a kind of imaginative collaboration from the viewer to interpret what they are seeing.”

However, it is the body of water (literally, metaphorically) filling each gown that encourages spiritual transformation. Water—as a passage between shelves of land—is inherently connected to transition: mortals and immortals alike have cleansed, purged and even re-birthed here, moving from one tangible or metaphysical place to the next. Although the actual water is not visible in Cowell’s images, it acts as an agent for movement and a deep, almost cosmic, setting for the garments. Inspired by scenes like Ada’s drowning in The Piano and Ophelia’s watery demise, the artist explains, “It’s the Romantic idea of the psyche unanchored and adrift in deep water that fascinates me.” In this way, aqueous infinitude becomes a chamber for the memorialisation of female transition. As woman and outfit are separated, they alight one another, passing through the rigor of ritual toward transcendence.

Laura Skerlj

TO THE SURFACE

Just as the wearing of a marvellous gown can transform a woman from mere mortal into princess or screen goddess, so an unremarkable female garment – a discarded petticoat found in a skip perhaps – is transformed by Meg Cowell in her photographs into an alluring presence, charged with the mysteries and paradoxes of feminine states of being. These luscious photographs are remarkable for the sense of their garments being inhabited not only by their absent wearer, but also by a complex of moods, emotions, constructs of the feminine and even characters. Is that Ophelia floating down to the dark depths in White Chalk?

The closest analogy to the suggestive power of female garments in these images is the film still of Marilyn Monroe in that dress. We forget the gowns in other iconic images of women, but we remember that one – its pleats, halter neck and shimmering lamé. Why? Because set in motion above the subway vent it becomes animated with the qualities of Marilyn herself: both the film persona - exuberant, irrepressible, insouciantly provocative; and the woman behind it - increasingly out of control.

The subjects of Meg Cowell’s photographs have this kind of charisma and understated double-edge - the result of her artful stitching, dyeing and arranging; her painter’s eye for colour and texture; and her ability to elicit a sense of movement by floating the garments in water. The dancing, light caressed, peach confection of a gown in Flush is the stuff of fantasy or fairy-tale, yet the smoky wisps and tendrils of its fragile underskirt – extraordinary in their painterliness - suggest an incipient process of osmosis, reminding us of water’s symbolic associations with transformation.

Victoria Hammond

MIRRORED PARTS, SACRED PLACES

The common thread running through discourses on beauty are most often based on the elements of clarity, symmetry, harmony and vivid colour. These properties are synonymous with geometric form and balance.

For the photographic work in ‘Sacrum’, Meg Cowell has embraced these principles. Her compositions have pleasing harmony and rhythm, gratifying the visual senses. Her aesthetic approach is based on proportion and structure where she amalgamates mirrored parts that fit harmoniously into a seamless whole, like a butterfly with splendid wings radiating out from the central thorax. These symmetrical arrangements around a central pod give the exhibition its title ‘Sacrum’, referring to the physical structure within the pelvic region.

Meg Cowell’s works are as ambiguous as they are structured. Through folds, seams, threads and bones she expresses a delicacy showing an internal world of sensuous places. The paired folds reveal an inner life of luscious drapes and enveloped spaces. This is a sacred place, a foramen, an orifice. Vividly translucent, light passes through texture, weave and skeleton in these sumptuous images, where one becomes intimate with the anatomy of lace and the lattice of bones.

The mirror imaging as a compositional device references the psychiatrist Rorschach’s inkblots, used to interpret personality characteristics in patients. Through her recent photographic work, there is evidence that emerging artist Meg Cowell has gained insight into her own creative character. The integration of emotional perception, creative intuition and her inquisitive sense of the psyche, reflects her developing maturity as an artist.

Through exploring a diverse range of evocative subjects, surreal topics and moody scenes, Meg Cowell is constantly developing intriguing bodies of work. This includes ‘Sacrum’.

Annabelle Collett